The Lights of Home

by Genevieve Yue

Chantal Akerman. News from Home. 1976–77. Feature film. 85 min.

This is an excerpt from Even no. 3, published in spring 2016.

In 1971, when she was in her early twenties, the filmmaker Chantal Akerman flew off to New York, having left her home in Brussels a few years earlier without a word. She stayed for two years, and in her new city she worked in a photography lab, posed as a life model, and ran the cashier at a porn theater. In those formative years, Akerman frequented Anthology Film Archives, where she saw avant-garde films by Yvonne Rainer, Jonas Mekas, and Michael Snow. She attended the premiere of Snow’s La région centrale (1971), a film that particularly impressed her, having been made with a camera mounted to a swinging mechanical arm. The camera’s movement was enough, Akerman remembered in a 2010 interview, to elicit “a state of suspense as tense as anything in Hitchcock.” A film didn’t need a character to organize a narrative, but could make the camera its protagonist, the camera’s movements its actions, and the experience of time the source of its tension.

Before leaving Belgium she had made Saute ma ville (1968), a short that bears the influence of Godard in its impish young heroine’s anarchic revolt against the drudgery of housework. (The star was Akerman herself, aged 18.) The films Akerman made during her New York period were more formally daring. In La chambre and Hotel Monterey, both made in 1972 in collaboration with cinematographer Babette Mangolte, the camera is the driving force. La chambre is especially indebted to Snow, and consists wholly of a rotating 360-degree pan around a small New York apartment. Sometimes we catch a view of Akerman lounging in bed, sometimes staring intently at the camera, other times toying with an apple.

By mid-decade she’d returned to Belgium and made Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), her most celebrated film, about a woman whose domestic routine includes preparing Wiener Schnitzel, washing dishes, and, once a day, turning a trick in her bourgeois apartment. Jeanne Dielman won Akerman international recognition, both for its formal austerity and its radical feminism; the film was made by an almost entirely female crew. Yet instead of building on the acclaim of Jeanne Dielman with another large-scale film, Akerman returned to New York in 1976 — where she shot News from Home, the film that most fully captures both her affection for her briefly adopted home and her family ties to her native one.

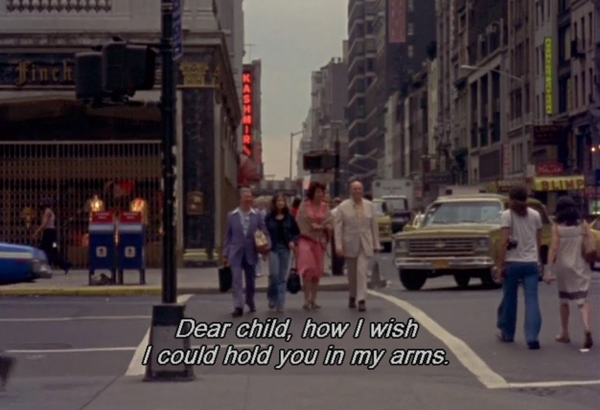

It is an acutely personal film, though in ways that might not seem immediately apparent. Akerman superimposes two moments, both of summer: from 1976, we see 16-millimeter footage of a sweltering Manhattan, and from 1971 we hear, in voiceovers read aloud by Akerman, letters sent from her mother Natalia Leibel Akerman, known as Nelly. The New York of News from Home is considerably grittier, more industrial, and less populated than today’s buffed, corporatized city, and yet at times it’s hard to tell whether New York was really so dusty and barren (in 1975 the city came within days of declaring bankruptcy) or whether Akerman was carefully staging her shots. The cinematography has the feeling of both deliberate selection and total banality. Akerman often took issue with the view that her long takes were somehow realist — “hyperrealist” was the term she preferred — and in News from Home the city appears unusually remote. Hardly anyone interacts with her. In an early shot, we catch her reflection, and that of a person that might be her companion, in a subway window. But no one speaks. Though the film’s soundtrack is crowded with the sound of passing cars, screeching brakes, and rumbling trains, the city is otherwise mute.

Nelly’s letters, meanwhile, are nagging and repetitive. They circle around a set of themes: the frequency of her daughter’s letters, the health of her husband and daughter Sylviane, her own fatigue in the summer heat, her plans to purchase a country home. She frets over her daughter — whether she’s happy, whether she has enough money, whether she’s lonely. She asks, sometimes, for pictures. Nelly ends every letter by telling Chantal how much she is loved and missed by her mother, father, and sister.

News from Home illustrates two of Akerman’s abiding concerns: distance and confinement. These are often entangled with each other. In Jeanne Dielman, the mise-en-scène is mostly limited to the home (as it is in many of her films), but offset by the implied critical distance of a steady, fixed camera view. In News from Home, the massive metropolis can feel just as restrictive. The wide-angle views of New York, and the passersby who, for the most part, do not interact with the young filmmaker, are countered by the intimate and insistent tone of her mother’s letters. Distance and confinement separate into channels of image and sound: we are distant from the city we see, and confined by the voice we hear.

With No Home Movie (2015), Akerman’s last film, the tension between distance and confinement is both revived and mollified. We see the filmmaker interview her mother, a Polish Jew, about her internment in Auschwitz. Akerman poses her questions with the same intense concentration exhibited in her earliest films, and in the grip of such observation, anything, be it city streets or domestic labor, may appear different, slower, or stranger. But we also see an intimate rapport between these two women, a selection from a lifetime of dialogue — through sound, if not in space. The daughter who once ran away to New York was never far from her mother, whether she wanted to be or not. When not filming in Nelly’s Brussels apartment, Akerman shows the Skype window through which they speak remotely. Their goodbyes are always prolonged, each unable to get off the line, and their voices are filled with tenderness.

Like the fort/da game described by Freud, the mother’s presence is guaranteed across a distance. For Akerman, this presence extends across her entire film career, sometimes inviting, other times intolerable, and often both. In News from Home it competes with the sounds of New York, eventually drowned out by the rush of passing subway cars in the film’s latter half. All of Akerman’s films have this divergence: a yearning for distance, whether Russia or Mexico or Israel, and the pull of home, the call of her mother’s voice. By the time of No Home Movie, though, Akerman had learned how to expand home so that it filled the space of the world, in part through the use of Skype to speak to Nelly from afar. “There is no distance in this world,” she tells her mother on the screen, her voice warm and content.

Nelly’s death in 2014 is only implied in No Home Movie, though palpably felt in the film’s bright, empty rooms. Last October, a few days before its American premiere at the New York Film Festival, Akerman took her own life. Perhaps the passing of her mother was the event that Akerman could not endure, the one thing that made this world unlivable. No home, no home movie.

In one of Nelly’s letters in News from Home, we learn that Akerman sent pictures back to Brussels during her New York sojourn, though we don’t see them. We might instead take the entirety of Akerman’s career as pictures sent from daughter to mother. Akerman once called Jeanne Dielman “a love film” for Nelly, because “it gives recognition to that kind of woman.” In a 2009 interview she added, “I made this film to give all these actions that are typically devalued a life on film.” In between the intolerable forces of distance and confinement is the space of this life, the place where women exist, where Akerman and her mother found a way to live. What Akerman teaches us is that cinema is one of the places where such lives can be esteemed and even flourish. It is also where living things might linger after they have departed.